|

Ancient Corinth was one of the most important city-states of ancient Greece. Today in the archaeological site, one can visit the Temple of Apollo; its seven remaining Doric columns stand in a prominent position overlooking the ancient Agora. The temple was built in 530 BC, consisting of 2 rooms, and originally had 15 Doric-order columns along its length and 6 along its width. The city market had a rectangular shape, housing a number of similarly laid-out stores, each divided into 2 rooms. Its front was consisted by a double row of columns, the outer Doric and inner Ionic. In the ancient Agora, one can also visit the shops where the Apostle Paul once stood, along with the ancient Council. Descending the steps of the ‘propylaia’ (front gates) will lead you to Lecheou street where you will encounter the Pirene Fountain, with its six cave-like chambers, and the Glauki fountain standing carved in the rock. In the archaeological site you will also have the chance to visit the Odeon, built in the 1st century AD; and the 18,000-seat theater built in the fifth century BC, and later converted by the Romans into an arena for animal fights. Finally, you can walk through the remnants of the gymnasium and Temple of Asclepius near the Lerna fountain. Above Ancient Corinth lies the Castle of Akrocorinth, the Acropolis of the ancient city, which is itself worth a visit. Places of interest near Corinth Itea (Greek: Ιτέα meaning willow), is a town and a former municipality in the southeastern part of Phocis, Greece. Built in the background of the Crissaean Gulf extends together with the neighbouring Kirra, along the coastline of the plain sharing the same name, the Crissaean Plain and it is the south ending up of the famous landscape of Delphi. It is a relatively new city, since it was founded in 1830 and it managed to become soon an important commercial and transit centre due to a series of favourable circumstances. The access to the city is easy, either by sea - it has a good port that serves the transport of both people and goods - or by land, as it is connected to the big road axis of Greece. It constitutes the way out to the sea not only for the Department - it is the port of Amfissa and Delphi - but also for the entire area of Central Greece. Galaxidi or Galaxeidi is a town and a former municipality in the southern part of Phocis. Modern Galaxidi is built on the site of ancient Haleion, a city of western Locris. Traces of habitation are discernible since prehistoric times with a peak in the Early Helladic Period (Anemokambi, Pelekaris, Kefalari, islet of Apsifia). A significant Mycenaean settlement has been located at Villa; the hill of St. Athanasios also revealed a fortified Geometric settlement (ca. 700 BC). In the Archaic and Classical periods (7th-4th centuries BC) was developed the administrative and religious centre at the modern site of Agios Vlasis. It seems that in ca. 300 BC the present site was settled and surrounded by a fortification wall; it is the period of the expansion of power of the Aetolian League. Haleion flourished throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods until the 2nd century AD. In an old mansion of Galaxidi are situated two museums: The Archaeological Collection of Galaxidi presents a collection, which was established in 1932 to host antiquities found and donated by citizens as well as excavation finds from the regions in and around Galaxeidi. The exhibition is organised in three main themes: (a) Private and daily life, (b) Trade and maritime activity and (c) Cemeteries. It focuses on the educational aspects as the finds are accompanied by pictures and texts, revealing the history of ancient Haleion, the precursor of Galaxeidi. The Maritime Museum of Galaxidi includes the Chronicle of Galaxidi, which was published by Konstantinos Sathas in 1865. It used to serve as a town hall for Galaxidi. The Chronicle of Galaxeidi is a Greek chronicle written in the year 1703 detailing the history of the town of Galaxeidi on the northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth and its wider region, including the towns of Naupaktos, Amfissa, and Loidoriki, from the Middle Ages to 1690. History Corinth’s settlement dates to 5000 B.C. which was discovered in the Korakos region, a testament to Corinthos’ habitation since the Neolithic Age. In antiquity, Korinthos was one of the largest and most important cities in Greece which had a key-role during the Peloponnesian War. After 200 B.C. became the capital of the Achaean Confederation. Under Julius Caesar it was elevated to the capital of the Achaia province. During the middle Ages it was associated with its impressive fortifications at Akrokorinthos (Acrocorinth). A powerful earthquake destroyed the city in 1858, which was rebuilt with earthquake resistant specifications undera new town plan, 9 km to the north of the ancient city. The town of Palaia Corinthos is situated on the site of Ancient Corinthos. Today, Corinth is located about 83 km west of Athens. The Municipality of Corinth had a population of 58,192, according to the 2011 census, the second most populous municipality in the Peloponnese Region, after Kalamata. It is surrounded by the coastal townlets of Lechaio, Isthmia, Kechries, and the inland townlet of Examilia and the archaeological site and village of ancient Corinth. Natural features around the city include the narrow coastal plain of Vocha, the Corinthian Gulf, the Isthmus of Corinth cut by its canal, the Saronic Gulf, the Oneia Mountains and the monolithic rock of Acrocorinth, where the medieval acropolis was built. Capital’s prefecture is the region’s prominent administrative, commercial, financial and cultural center. The city center has wide roads, parks, squares and a picturesque port with fishing boats. Beautiful pedestrian walkways entice the visitors for a stroll, coffee and shopping, with monuments, museums and historical sites surrounding the city. Delphi Delphi was a most known religious and cultural place in antiquity, being a Panhellenic temenos and a famous oracle in ancient Greece. It is indicative how both the myths and ancient sources refer to Delphi as the center of the world, lying at the foot of Mount Parnassos in a spectacular landscape with an overview of the Itea Bay. The archaeological site includes two sanctuaries dedicated to Apollo and Athena Pronaia. Apollo was the main deity worshiped in Delphi and his cult was established in the eighth century BC almost simultaneously to the first building activity in the sanctuary. The myths refer to the foundation of the sanctuary by Apollo, when he arrived transformed into a dolphin and call him Delphinios. Another myth reports Apollo Pythios to have killed the serpent Python that guarded the original temenos of Mother Earth; the famed Pythian Games celebrated this death and honored Apollo with musical and athletic festivities. By the sixth century BC the Pythian festival had become almost as popular as the famed Olympic Games, following the growing religious influence of Delphi throughout Greece. The music contests took place at the theatre, which was first built in stone in the fourth century BC and was subsequently refurbished several times. Its present form dated to the third century BC could host around five thousand people. In 582 BC athletic events, almost similar to the Olympic ones, were also included to the Pythian Games. Since the fifth century BC they took place at the stadium, which was higher up the slope and is well preserved nowadays in the form it was built in the second century BC. The names of the winners on the bases of their statues, as reported by Pausanias, prove the Panhellenic participation in these Games. Supporting this, the Pindar’s Odes praise the Pythic winners and more particularly, the chariot race winner Iero, tyrant of the Sicilian city of Gela. Polyzalos, also a tyrant of Gela dedicated to Apollo the famous bronze statue of a Charioteer after his victory at a chariot race of the Pythian Games. Another wealthy votive offering was that of Daochos II. It consisted of nine marble statues, all members of Daochos’ family who were winners at the games in Delphi. Both statues are on display in the Delphi Archaeological Museum of Delphi. Delphi was regarded in antiquity as the most trustworthy oracle and both ordinary people or prestigious rulers and cities consulted it. The divination and other cult rituals took place in the temple of Apollo and more particularly in the adyton, where also a statue of Apollo and the omphalos, symbol of Delphi as the center of the world, were housed. According to the legend, there were five different temples of Apollo built before the existing one, an imposing Doric temple completed in 330BC and nowadays standing on a central terrace and partially restored. The oracle grew in fame especially during the archaic colonization, when the Greek metropoleis seeked for approve of the God before founding a colony, enhancing the religious ties between the cities. It is indicative of its political power the fact that the Oracle continued to monitor the colonies after their establishment. In the course of the seventh century the oracle’s fame reached from Magna Graecia to the west to Minor Asia to the east. The Oracle reached its peak between the sixth and the fourth centuries BC, when numerous votive offerings from around the Greek world were dedicated to Apollo as a sign of gratitude for his guidance or in occasion of important events, such as war victories or wins at the Pythic Games. Most votive offerings stood along the so-called Sacred Way, a road that pilgrims and visitors followed through the temenos until they reached the temple of Apollo. Amongst others stand out the Treasuries, small buildings in the shape of a temple, built by cities in order to safe keep their offerings and display their wealth and prosperity to the visitors of the sanctuary. There were several Treasuries in the sanctuary reported by sources, including the earliest one dedicated by the Corinthians, and the Treasury of the Massaliots, built in order to enhance the increasing commercial power of this colony. As in both these situations, not all the treasuries have been identified in the ruins with certainty or are clearly visible. One of the wealthiest monuments in the sanctuary was the treasury dedicated by the people of Siphnos, the most prosperous of the Greek islands in the sixth century BC. It was made of Parian marble and had an admirable relief decoration. Although the Treasury is only preserved on the foundations level, its sculptures are on display in the Archaeological Museum of Delphi. The most dominant Treasury along the Sacred Way is that of the Athenians, built around 500 BC as a symbol of the victory of democracy over tyranny or in memory of the victory of the Athenians against the Persians in Marathon (490 BC). It had the shape of a small Doric temple in antis and according to literary sources, it contained trophies of several Athenian war victories including the battle of Marathon. It was restored so that nowadays it stands out at the archaeological site. It was famous for its elegant relief decoration with mythical scenes of the Greek heroes Theseus and Hercules; the original sculptures are on display in the Archaeological Museum of Delphi. The archaeological site of Delphi also includes a sanctuary dedicated to Athena Pronaia. Within its boundaries among altars and several cult buildings, there were the famous circular Tholos and the remains of three temples dedicated to the goddess, two archaic ones and one dated in the fourth century BC. There has been archaeological research in Delphi since the 19th century in both sanctuaries. The Archaeological Museum situated at the site presents their history by displaying the finds in thematic units. Olympia

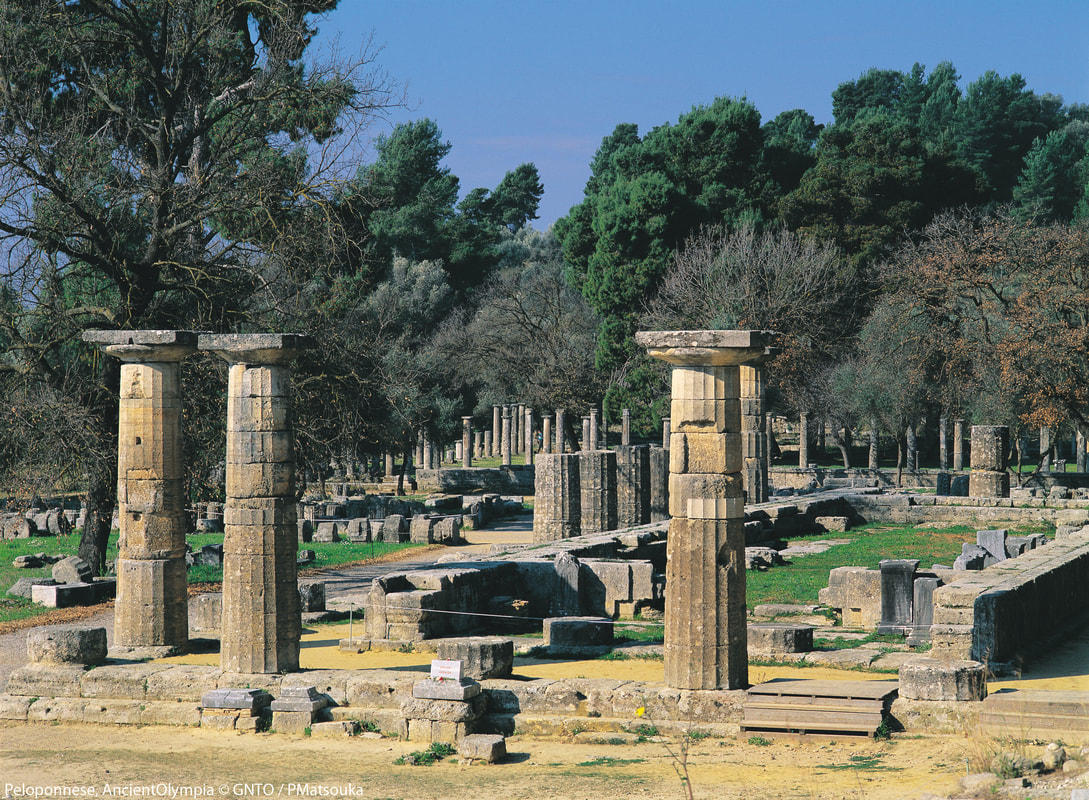

A sanctuary of ancient Greece in Elis on the Peloponnese peninsula, is known for having been the site of the Olympic Games in classical times. The most celebrated sanctuary of ancient Greece lies in the beautiful valley of the Alpheios river. Dedicated to Zeus, the father of the gods, it sprawls over the southwest foot of Mount Kronios, at the confluence of the Alpheios and the Kladeos rivers, in a lush, green landscape. Although secluded near the west coast of the Peloponnese, Olympia became the most important religious and athletic centre in Greece. Its fame rests upon the Olympic Games, the greatest national festival and a highly prestigious one world-wide, which was held every four years to honour Zeus. The origin of the cult and of the festival went back many centuries. Local myths concerning the famous Pelops, the first ruler of the region, and the river Alpheios, betray the close ties between the sanctuary and both the East and West. Remains of food and burnt offerings dating back to the 10th century BC give evidence of a long history of religious activity at the site. No buildings have survived from this earliest period of use. The first Olympic festival was organised on the site by the authorities of Elis in the 8th century BC – with tradition dating the first games at 776 BC. The classical period, between the 5th and 4th centuries BC, was the golden age of the site at Olympia. A wide range of new religious and secular buildings and structures were constructed. During the Roman period, the games were opened up to all citizens of the Roman Empire. The 3rd century saw the site suffer heavy damage from a series of earthquakes. Invading tribes in 267 AD led to the centre of the site being fortified with material robbed from its monuments. Despite the destruction, the Olympic festival continued to be held at the site until the last Olympiad in 393 AD, after which the Christian emperor Theodosius I implemented a ban. The archaeological site is located withing walking distance of the modern village called Ancient Olympia and it includes ruins from Bronze Age to the Byzantine eras. The site covers an expanded area of ruins scattered among low trees, as well as the ancient stadium where the Olympics took place. An impressive array of artefacts, which were unearthed during excavations, is an exhibition at the nearby Olympia Museum. |